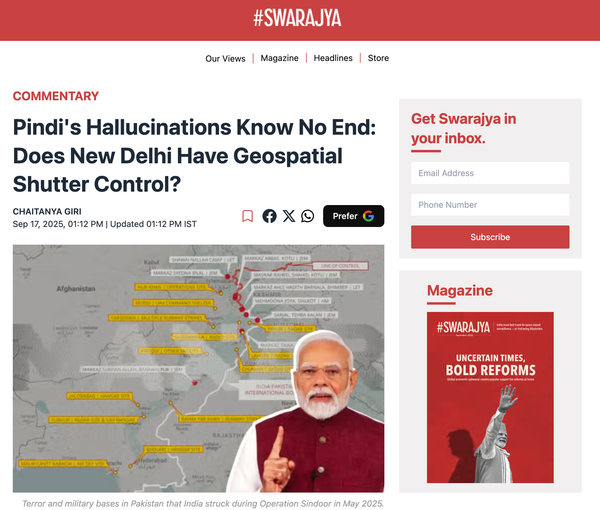

Geospatial Shutter Control: India’s Task in Security Council

India is responding to the Chinese aggression on the entire Indo-Tibetan landmass, spanning from the Wakhan Corridor to Arunachal Pradesh, through various means. Our democratic, social, and mainstream media have begun reporting on the strategic conflict extensively. The country has not procrastinated this time in realising that China will sooner or later extend its colonialist war by fighting both military and informationized battles. As a result, a growing number of recent news and analytical reports in India are accompanied by commercial geospatial datasets and satellite imagery (GD&SI). The use of GD&SI for reporting-based analyses is not a new concept. The first-ever use dates to April 29th, 1986, immediately after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Soviet Union, when journalists and analysts from all over the world were keen to report the extent of damage caused by the accident and raise the liability account to corner the then Soviet leadership. However, the Iron Curtain limited such on-the-ground reportage, as did the large exclusion zone resulting from the nuclear radiation. It was then that the United States Geological Survey’s LANDSAT 5 became the first civilian-commercial remote sensing satellite to take images of the accident site, three days after the incident. France’s Spot Image company had launched the SPOT-1 satellite in February 1986. It delivered a superior resolution (10-meter) satellite image of the accident site a few days later.

This practice was next used in a big way during the 1991 Operation Desert Hell when the same LANDSAT took images of the numerous oil wells lit on fire by invading Iraqi forces in Kuwait. Despite these successful commercial technology demonstrations, satellite-driven reporting did not flourish easily. It was seldom used by Western investigative analysts to report on the clandestine military programs of Iran, North Korea, Russia, and China. Reports that made it to the media were based on a few publicly released images and a concerted narrative, aided by intelligence agencies. Otherwise, many national geospatial agencies were impeding the widespread and unabated sale of commercial GD&SI on the basis of national security ramifications, a policy commonly referred to as ‘Shutter Control’. The recent use of geospatial analyses on Indian social and mainstream media has been made possible due to the declining cost of earth-observation satellite construction and launch, the availability of easy-to-use imagery and data, and a subscription-based business model that is affordable to financially modest independent geospatial specialists. None of these media-released images is coming from ISRO or private Indian satellite imagery companies. These Geospatial Satellite as a Service (GSaaS) solutions are emerging prominently from MAXAR and PLANET, two US-based, renowned commercial geospatial companies. GSaaS specialists are collaborating with journalists, independent political and military analysts, and media companies to analyse the developments in the conflict zone. These efforts are enhancing commoners’ knowledge of the Galwan Valley, the Shyok River, the G219 Highway, the Leh-Daulat Beg Oldi Road, Skardu, and even Pangong Tso’s Eight Fingers, which, until now, were merely a beautiful desert landscape behind the azure waters of the lake. But shouldn’t India consider controlling the shutter over such GSaaS, particularly now that the entire Karakoram-Himalayan Belt is becoming a geopolitical cauldron? The answer is nuanced. No sensible country ideally wants its strategic installations regularly mapped by satellites of other countries. Yet, both friendly and adversarial countries cannot resist prying into each other's affairs, which is an acknowledged fact. Such prying by states can be managed through diplomacy. What cannot be managed is snooping by malicious non-state actors, as they now have access to easily available and inexpensive commercial GD&SI. Hence, shutter control is justified. Data sells, and cheaply available data sells even more. Regulating easily and cheaply available, rich (in terms of information and intelligence), commercial satellite imagery and data under the premise of shutter control could be a tricky affair, particularly when the data providers are of overseas origin and sell the data globally. Likewise, enforcing such regulations on domestic companies will be detrimental to India’s aspiration to establish a globally competent private GSaaS industry, particularly when it has vowed to draft a liberal domestic geospatial policy. Although there is no public discussion on this topic nor in India’s strategic circles, a liberal geospatial policy announcement should not close the door on shutter control. Hitherto, there is scope for soft shutter control, and this is how it can be done.

On the domestic front, India’s foremost national geospatial agency should be empowered to purchase all private-commercial geospatial datasets generated, perhaps at a subsidised rate, and be a perennial customer or subscriber of all private geospatial companies operating in India. The agency can then get into a binding agreement where it obligates the companies to warp the images and datasets of certain security-sensitive geographical coordinates within the country. The filtered, shutter-controlled GD&SI can then be permitted for commercial sale without further restrictions. Such a soft domestic shutter control can address security concerns while also facilitating the much-needed commercial progress of the domestic geospatial industry. The next challenging step for India is to convince partner countries to sign on the dotted line. This can be initiated with the third and final of the strategic foundational agreements with the United States – the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA). The India-US BECA Agreement is principally based upon the exchange of military-grade geospatial, nautical, topographical, and aeronautical data between the two countries. Commercial GD&SI are likely out of scope in the current draft of BECA.

Nonetheless, New Delhi should call for a clause in the BECA draft that requests Washington to blur out zones and coordinates sensitive to India from the commercial imagery generated by US-based geospatial companies. In return, New Delhi should offer reciprocal blurring of sites sensitive to US interests, as well as commercial GD&SI generated from Indian-origin companies. Simultaneously, now as a temporary member of the United Nations Security Council (2021-2022), India should envisage putting forth a multilateral United Nations Protocol, binding to all member states, where countries are asked to implement soft shutter control only to prevent GD&SI falling in the hands of malicious non-state actors and preventing the consequential utility of GSaaS for cross-border terror, organized crime and illicit activities. With the Indian government’s recent liberalisation efforts, many of the policy-level impediments of private and commercial Indian GSaaS companies will soon be ironed out. However, such a policy should also, without hindering their business growth, reflect India’s emerging national security demands. Analytical reports that use commercial GD&SI provide the necessary proofs and validations for activities that cannot be reported from the ground. The newfound fête for GSaaS in India’s free media is here to stay. If India is to unravel the distortions in its neighbourhood and shape narratives, it should also utilise this media-GD&SI collaboration to substantiate environmental and human rights violations to the fullest. The ongoing conflict on the Indo-Tibetan landmass is a good starting point.

The original piece was published by NewsBharati.